Do you know what language is the official language in the USA? languages of america

Do you know what language is the official language in the USA?

If your answer sounded "English", try a couple more times.

Do not be upset: almost everyone we interviewed answered the same way.

English is called by default, because. it is the most spoken language in America. But, it has a competitor - Spanish, which is slightly behind English, is the second most common, thanks to 40 million Hispanic Americans.

Therefore, some may ask: “Why is it that the United States of America, which is (in your opinion) an English-speaking state, puts up with such a state of affairs (which includes not only Spanish, but also many other languages), which we can even know nothing?" The answer is simple: "The government of America has never adopted English as a state or official language." Moreover, despite numerous attempts by various organizations to do so. For example, in 1870, a certain John Adams proposed that the Continental Congress of the United States of America adopt English as the state language. Such a proposal received a verdict of "anti-democratic and posing a threat to individual freedom." The debate about whether English is needed as a single state American language has been going on for many years, but the answer to this question has not been found. Despite this, in 27 states (out of 50) English is accepted as official.

The current situation is connected, first of all, with the history of this state. It should not be overlooked that since 1776 the United States has been a multiethnic country. Even then, it did not seem strange to anyone that about twenty different languages were in common use. And foreign languages competed for the right to dominate the country: like English, German, Spanish and French. To date, 322 languages are spoken in the United States, 24 of which are in circulation in all states and in the District of Columbia. The largest number languages is in circulation in California - 207, and the least in Wyoming - 56.

So what is the reason Congress will not declare any one language as the state language? And all because the United States is a nation of immigrants and the above information confirms this fact. That is why giving official status to one language would infringe on the rights of full-fledged citizens who do not fully speak English.

To support such citizens, the “Act on civil rights 1964". Although English is recognized in 27 states official language but, nevertheless, they also have to comply with the provisions of this Act, according to which all important documentation must be written in all languages of those citizens who receive any privileges from the government.

Besides, this document requires that all public economic organizations that receive financial support from the state keep documentation in all languages of their clients. You will ask why?" The answer is the same: "America has never adopted a single official language, which is clearly indicated in this legislative act."

In addition, this law works not only at the level of documents. Today, for example, most of the commercial structures operate in English and Spanish - "hot lines" are served by operators who speak them, and almost all instructions (for example, inscriptions in public transport) are also dubbed in 2 languages.

This state of affairs is also reflected in the work of the United States translation agencies. Statistically, the most popular type of translation in America is from English to Spanish.

The article was prepared based on materials from various Internet sources "foreign languages".

Languages of the Americas quite varied. Conventionally, they can be divided into two large groups: the languages of the Indian tribes that inhabited the Americas before the European conquest and the languages that spread in the Americas in the post-colonial period (mostly European languages).The most popular languages in America today are the languages of European states that once had extensive colonies in America - these are English (the country of Great Britain), Spanish (Spain) and Portuguese (Portugal). It is these three languages that in most cases are the official state languages of the countries of Northern and South America.

The largest and most widely spoken language in America is Spanish. In total, more than 220 million people speak it in the Americas. Spanish is the dominant language in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Uruguay, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Panama. It is also the official language in these countries.

In second place in terms of distribution in America is English (more precisely, its American dialect). It is spoken by 195.5 million people in the Americas. Most English is spoken, of course, in the United States. It is also spoken in Jamaica, Barbados, Bahamas, Bermuda and other island nations. English is also considered the official language of Belize, although the majority of the country's population still speaks Spanish and Indian languages.

Rounding out the top three, Portuguese is spoken by 127.6 million people in the Americas. Most Portuguese is spoken in Brazil. In this country, it is the official language.

French is also popular in America, it is spoken in both Americas by 16.8 million people, German (8.7 million people), Italian (8 million people), Polish (4.3 million people). .) languages.

As for the Indian languages, they are spoken today in both Americas by about 35 million people. Most Indian languages are spoken in Peru (7 million people), Ecuador (3.6 million people), Mexico (3.6 million people), Bolivia (3.5 million people), Paraguay (3.1 million people)

The Indian languages of America are quite diverse and scientists are divided into groups according to geographical principle. most big group Indian languages is the "Ando-Equatorial" group of families of Indian languages - the languages of this group are spoken by the tribes of Quechua, Aymara, Araucans, Arawaks, Tupi-Guarani, etc. - more than 19 million people in total. The languages of the Penuti family group are spoken by the Indians of the Mayan tribes, Kaqchikels, Mame, Kekchi, Quiche, Totonaki, etc. - a total of 2.6 million people. The languages of the "Azteco-Tanoan" group of families are spoken by the tribes of the Aztecs, Pipili, Mayo, and others - about 1.4 million people in total. In total, in both Americas there are 10 Indian language groups of families.

Part III. Languages of six continents

1. Large and small languages of the world

Our book is almost finished. On its pages you met the names of many different languages and learned a lot about them: about their close and distant relatives, about their history, about vowels and consonants, suffixes and transfixes, grammatical categories and constructions - you can’t list everything at once. But how are these languages, including those already familiar to us, distributed throughout our land? What languages live in America, what - in Asia, what - in Australia? How are neighboring languages similar to each other and how do they differ? About this - albeit in a few words - I would like to tell you in the end (adding to what was said about large language families in the second chapter).

There are at least five thousand languages on earth. Some scholars believe that their number is even greater - six to seven thousand. No one knows the exact number - firstly, because such a number cannot be exact (after all, much depends on how you count, and we remember that it is sometimes difficult to draw a line between a language and a dialect); secondly, because there are languages that have not yet been discovered: imagine, somewhere in the Amazon jungle there lives a people who speak their own special language, and not a single linguist in the world has any idea about this language. Is it really interesting? What if just in this language all the words are from the same vowels? Or no verbs at all? Or words can stand in two cases at once - nominative and genitive? Or is it not necessary for every word to have a root? Can't be, you say? But what if?

So, at least five thousand languages. Among them there are great, world languages - they are spoken by hundreds of millions of people. And there are small languages - well, for example, languages for only one thousand speakers or even one hundred people. It is very difficult for such languages to survive surrounded by their more numerous neighbors: they are on the verge of extinction. With each successive generation of people speaking them, there are fewer and fewer people, they gradually switch to another, more common language of their neighbors - and now the moment comes when no one speaks this language.

Many languages died this way hundreds and thousands of years ago; among them were very famous ones, such as Sumerian, Hittite, Akkadian (all in Asia Minor), Etruscan (northern Italy) or Gothic (Western Europe); but even more were those of which there were not even names left. Ainu (the mysterious language of the natives of the north of Japan and Sakhalin Island) and Ubykh (a kindred Abkhazian language of a small people who lived Lately in several villages in Turkey) disappeared right before our eyes: last person, who spoke the Ubykh language, died quite recently, in the early 90s of the XX century.

Linguists try very hard to describe such languages in time - after all, each language is unique. But there are a lot of languages that are now on the verge of extinction, so many that Russian linguists even recently published the Red Book of Russian Languages \u200b\u200b- as Red Books are published by biologists with a description of endangered plants and animals. There are many languages in Russia that are on the verge of extinction, especially among the languages of the peoples of the North and Siberia. For example, at the end of the 20th century, only one elderly woman remembered the Kamasin language (there was once such a Samoyedic language in Siberia, close to the Selkup language).

Meanwhile more than a half of all the inhabitants of our planet speak one of the five largest languages of the world, and the largest, or world languages, can be considered languages spoken by more than two hundred million people. So:

Chinese - more than a billion speakers;

English - more than four hundred million;

Spanish - more than three hundred million;

Hindi - about three hundred million;

Russian - more than two hundred and fifty million.

In addition, there are languages close to the world - they are spoken by one hundred to two hundred million people. These are primarily Arabic, Portuguese, Indonesian, Bengali, Japanese, German and French.

And now we will travel to different continents to find out where which languages live.

2. America

In general, America is one of the largest and most populous parts of the world, and the number of languages coexisting with each other in its territory is amazingly large. However, people in America appeared relatively recently - this, of course, by historical standards, recently, but by our human standards, a very long time ago, about ten thousand years ago. So if, for example, in Africa or Asia, people have lived since ancient times - one might say, always, then they came to America, or rather, they came. They came through the Bering Strait, which at that time was not a strait, but a strip of land, and in this way, like a bridge, people moved from Asia to America. Who these people were and what languages they spoke is unknown. Moreover, it is also unknown whether they came once or several times; most likely different groups of immigrants crossed the "Bering bridge" in different time- so to speak, "waves", one after another.

America, as you know, can be North, Central and South - it is worth talking about each of them separately.

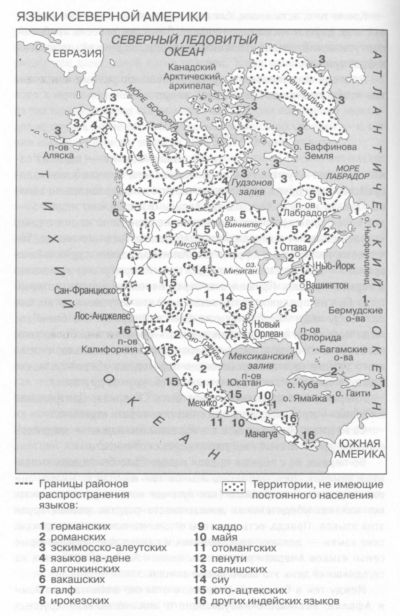

North America.

Its indigenous peoples, the Indians, have two amazing linguistic features.

First, it could rightfully be called a "mosaic of languages". Indeed, there are not just many languages, they are also surprisingly different (like pieces of a puzzle) - for example, there is no convincing evidence of relationship different groups these languages. True, there are hypotheses that almost all American languages - distant relatives, and even that some families of American languages are related to the languages of Asia, but, I repeat, today these are just hypotheses.

Meanwhile, in North America, unlike again in Asia and Africa, there is no one or more major languages or even language families - such as, for example, Chinese or the Bantu languages: in a sense, all American languages in this respect they are comparable to each other (again, like colored glass in a mosaic).

Finally, all these languages are wonderfully mixed together! Indeed, the usual picture of the distribution of languages in some territory looks like that there are related or at least similar languages nearby. Moreover, this should be expected in the case when there was a consistent settlement of the territory - but there is nothing like this in North America: there, quite often, neighbors turn out to be languages belonging to completely different families and having completely different systems, which means that two neighboring languages can differ from each other no less than, for example, Swedish from Chukchi (and if one of our readers has forgotten what is the difference between analytical Swedish and incorporating Chukchi, let him look into the sixth chapter!)

Other important feature lies in the fact that the languages of the North American Indians relatively little influenced each other and just as little succumbed to the influence of other languages. Despite the fact that Indians of different tribes and peoples lived side by side for centuries (and they have similar customs and dwellings, similar clothes, the same cuisine), their languages almost did not mix, which, of course, is due to some features of their life. After all, these proud and warlike tribes and peoples, as a rule, were at enmity among themselves, and during peaceful respite, they had sign language as a universal language of communication. This attitude towards neighboring languages was preserved later. Several centuries have passed since the time of Columbus and Cortes, the Indians have been living together with Europeans (especially with the Spaniards) for a long time. In a normal situation, the Spanish language should have become more prestigious and somehow influenced at least the vocabulary of the "subordinate" languages, but this did not happen with all languages. Until now, there are many Indian languages in which the number of borrowings from Spanish is extremely small: only a few dozen words.

The fate of the North American Indians, as is known from history, is very tragic. They were forced out of their ancestral lands by Europeans; many peoples (and languages) have died out completely, and most others are on the verge of extinction. The traditional culture of these peoples, whose way of life turned out to be incompatible with modern technical civilization, also almost completely perished.

It is very difficult to list even all the language families of North America (not to mention individual languages) - in addition, linguists often disagree on which language should be attributed to which family. But to give you an idea of the degree of diversity in the North American linguistic picture, I will call on Henry Longfellow for help. You probably know that this American poet wrote the famous "Song of Hiawatha" in the middle of the 19th century, which Ivan Alekseevich Bunin translated into Russian in beautiful verse in the 20th century. So, this poem begins with the fact that Gitch Manito, the Lord of Life, tired of endless human strife, lit the Pipe of Peace, calling all nations to council. And people responded to his call:

Along the streams, across the plains,

There were leaders from all nations,

There were Choctos and Comanches.

There were Shoshone and Omogi.

There were Hurons and Mendens,

Delaware and Mogoki

Blackfoot and Pony

Ojibway and Dakota

We went to the mountains of the Great Plain,

Before the face of the Lord of Life.

This passage lists twelve indigenous peoples of the Americas. Of course, twelve is an insignificant number in comparison with all the linguistic diversity of Indian languages; nevertheless, let's see what these languages are. Some names are given in "Songs ..." in an outdated transcription - we will use the new ones adopted now. So, the Choctaw language, or Choctaw, is a representative of the Gulf (Gulf of Mexico) family, which also includes languages such as Chickasaw, Muskogee and Seminole (yes, Osceola - the leader of the Seminoles spoke that very language!). The Comanche and Shoshone languages are part of the Uto-Aztec family (Mexico and the southern United States), that is, the warlike Comanches are distant relatives of the famous Aztecs (other languages of this group: Ute, Hopi, Luiseño, Aztec / Nahuatl, Papago, Tarahumara, Kaita, Kora, Huichol). The Omaha, Mandan, Dakota languages are all members of the Sioux family (the central and western regions of the United States; the languages of Iowa, Assiniboine and Winnebago are also included). The Huron and Mohawk languages are part of the Iroquois family (Great Lakes region; other languages of this family are Onondaga and Cherokee). Delaware, Blackfoot (Bunin translated the name of this people literally: Blackfoot) and Ojibwa - Algonquian languages (center and east of the USA; Cree, Menominee, Fox and extinct Mohican also belong to this family - remember the story "The Last of the Mohicans" by Fenimore Cooper?) . Finally, the Pawnee language is one of the Caddoan languages (together with the Caddo language; they are close relatives of the Iroquois).

Therefore, this passage mentions twelve languages of six different families. Try, as an experiment, to imagine the Lord of Life lighting his pipe in, say, Russia - it will be quite difficult for you to name twelve different languages right off the bat, and even representatives of six different families (not groups and subgroups!), and to get together together, such peoples will have to go a long way. Meanwhile, the Indian tribes gathered together precisely in order to put an end to mutual hostility - and therefore, these peoples could not help but know each other, since they fought. And after all, these are far from all the languages that the poet could mention: naming other (also far from all) languages of these families, I listed at least twenty more languages - so we could complicate our experiment and try to collect not twelve, but thirty-thirty-five languages of Russia. But after all, these are not even all the families of Indian languages, there are also many more families: here the Salish, Wakash, and finally Apache languages (from big family Na-Dene - speakers of the Na-Dene languages are believed to be among the last to come to America from Asia), the Penuti languages, and many others.

The families of North American Indian languages are quite different (although many of them are characterized by incorporation and complex alternations) - remember, we said that the languages of different Indians in general differ from each other much more than the culture of different Indians. And literally about each of the families one could say something wonderful.

Well, for example, the Apache languages. Among them there is such a language as Navajo. This is the largest language of the Indians of North America and is quite alive: now it is spoken by about one hundred and forty thousand people, that is, about the same as Kalmyk (about one hundred and fifty-six thousand according to the 1989 census), Tuvan (about two hundred thousand according to the 1989 census years), and only slightly less than in Icelandic (about two hundred and fifty thousand).

The Iroquois languages are not very numerous, but certainly one of the most famous languages in North America, and the most famous of them is probably the Cherokee language. It was for this language that an Indian named Sequoyah (who did not know English!) invented a special script in the 19th century.

As for the Algonquian languages, many of the Indians who spoke them lived on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean and were the first of the Indian tribes that Europeans met. It was from these languages that words describing the life of the Indians got into all the languages of Europe: wigwam, moccasins, totem, tomahawk, etc. It is clear that far from all Indian tribes the dwelling was called the word wigwam - Iroquois, Apaches, Sioux and other non-Algonquins, Of course they called it something else.

I hope that now you have got some idea of the real diversity of Indian languages and their, so to speak, "density" - after all, the territory of North America, in general, is not so big. Recall that the nomadic Indian tribes and located on the map will be completely disordered - this creates an even more impressive linguistic picture of the region.

In addition to the Indians, the Eskimos and Aleuts also live in North America. Their languages are not related to the Indian languages, but are related to the languages of ours, Asiatic, Eskimos and Aleuts, as well as the language of those Eskimos who live in Greenland. These languages are also closely related to each other, although the inhabitants of different countries who speak them still do not understand each other. These are bright representatives of incorporating languages with complex grammar.

Central America.

This is a completely different country, and other Indians live in it, not like those with whom we have just met. They did not roam the prairies, hunting for bison, but created beautiful cities and statues, built pyramids. They did not know the wheel and iron, but they used amazing accurate calendar, were able to observe stars and planets and invented writing - icons-drawings similar to hieroglyphs. There are two most famous languages here: Maya and Aztec, which, by the way, both have successfully survived to this day. These are different languages, they belong to different language families. Once upon a time there were two states: the Mayan state on the Yucatan Peninsula and the Aztec state in the mountains, both in what is now Mexico. The empire of the warlike Aztecs kept many other Indian tribes and peoples in subjection. If you have read the novel "The Daughter of Montezuma", then remember that in those days the Aztecs were subordinate to the Otomi people. The Otomi language has also survived to this day; it is not related to the Aztec and belongs to another, rather large, Otomang family. And the Aztec (or Nahuatl, as it is now called), as you remember, is part of a large Uto-Aztec family, common not only in Mexico, but also in the current United States. The Aztecs, conquered by the cruel Spaniard Cortes, were also one of the first Indian peoples encountered by Europeans; therefore, it was from the Nahuatl language that the words chocolate and tomato, now known to everyone, penetrated into Spanish (and then into many other languages).

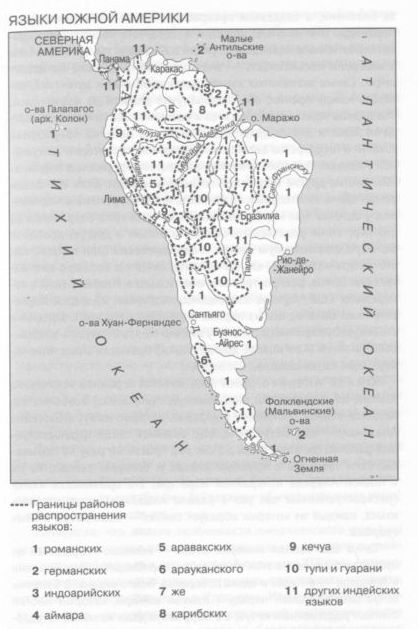

South America.

Here, too, there are a huge number of languages, but they are perhaps the least explored. This is especially true of the languages of those tribes and peoples who live in the Amazon basin - there, of course, there are still such hard-to-reach areas where Europeans have simply never visited. Speaking of major languages and large families, then there are at least three of them in South America. These are the Arawakan languages (distributed just in the Amazon region) and two large languages, each of which forms a family, the Quechua language and the Guarani language.

Quechua was the language of the Inca Empire - a great state before the arrival of the Spaniards. This language is still spoken in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador - in the Andes and along the Pacific coast. In Bolivia, Quechua is spoken along with the Aymara language, which is considered by many to be related to Quechua; and in Peru, Quechua is even the official language, along with, of course, Spanish.

Guarani, on the contrary, is the language of the eastern part of the continent. It (and its related Tupi language) is understood over a wide area from Argentina to Brazil; it plays a particularly significant role in Paraguay (where even the national currency is called the guarani).

The fate of European languages in America. America has four European languages - English, French, Spanish and Portuguese. All these languages are official in different countries America and actually dominate the continent.

First of all, this concerns in English and two countries in the North of America - the USA and Canada. In these countries, the dominance of the English language is almost undivided, because the languages of the Indians are practically not spoken there. However, the English spoken in America is quite different from what is called "British" English. If any of you have heard Americans speaking English, he will agree that this language can rightly be called "American English". First, you probably noticed the peculiarities of the pronunciation of Americans. If the listener is familiar only with the British version, then his first impression of the speaker is that he has, as they say, "porridge in his mouth." In fact, the fact is that the American system of sounds is just somewhat different than in European English, for example, some sounds do not differ - say, an American pronounces the words sor (cop - "police") and sir (cap - "cup") the same way. Other sounds are pronounced differently than in Britain.

Secondly, often a word is translated differently into British English and its American version. For example, to hire (rent) "in British" will be to hire, and "in American" - to rent, gasoline in Britain is usually called petrol, and in America - just gas, etc.

It is interesting that many features of the American version are often explained by the influence of ... the Irish version of the English language. The fact is that in the second half of the 19th century, America was swept by a wave of Irish emigrants fleeing the famine that raged then in Ireland. By the way, note that among the heroes of American literature, the Irish are not so rare - always brave, noble, with good feeling humor, proud to the point of arrogance (however, some of them loved to brag). Remember, for example, who was Maurice Mustanger, the hero of Mine Reed's novel "The Headless Horseman".

Within the United States itself, many dialects are distinguished: an American will always distinguish, for example, the speech of a southerner from the speech of a resident of the Midwest or the Atlantic coast.

In addition to English in North America, there is also French and Spanish - all of these, in fact, were the languages of the European conquerors. English has pressed them hard, but they do not give up. So, in the beginning, France had very significant territories both in Canada and in the present USA, but then England began to conquer and select them. Nevertheless, the French, having made efforts not to be completely expelled, nevertheless remained in America, although they now live in only one Canadian province - Quebec (in the east of the country). It is in it that one of the largest cities in Canada - Montreal is located. Quebecers speak French and even want to gain independence and separate from the rest of Canada. By the way, Canadian French is also different from European, although the difference is much smaller than between English and American. Somewhere in Paris, the Canadian accent is heard and perceived in much the same way as in Moscow - the peculiarities of the Ryazan or, say, Vologda pronunciation.

Spanish is not a state language in North America, but it is quite common in the south of the United States - in the territory that was once taken away from Mexico, that is, primarily in the states of Texas, Arizona and California. Then it was believed that over time, English will "win" Spanish and Spanish will disappear, it will be forgotten. But this did not happen - on the contrary, today this language is alive here and is used quite actively: for example, newspapers are published in it, and the number of speakers is even growing.

And finally latest language, which should be mentioned here is the so-called Black English. It is spoken in North America by some of the descendants of immigrants from Africa, and this language has not only a different system of sounds than British and American English, but even a different grammar. It began to be studied in the 60s of the XX century, and the famous American linguist, one of the founders of sociolinguistics (look again at the third chapter!) William Labo'v became the discoverer of Black English.

In Central and South America, the main state languages were not English and French, but, on the contrary, Spanish and Portuguese - after all, almost all these territories were once colonies of Spain and Portugal (France, England and Holland had only very minor possessions here). At the same time, the Portuguese language is accepted only in one, but the largest country in South America - in Brazil; in terms of area, this country ranks fourth in the world. In almost all other countries, Spanish is considered the official language, sometimes along with Indian languages (as in Peru). American Spanish and Portuguese also differ from European ones, but not as much as American English.

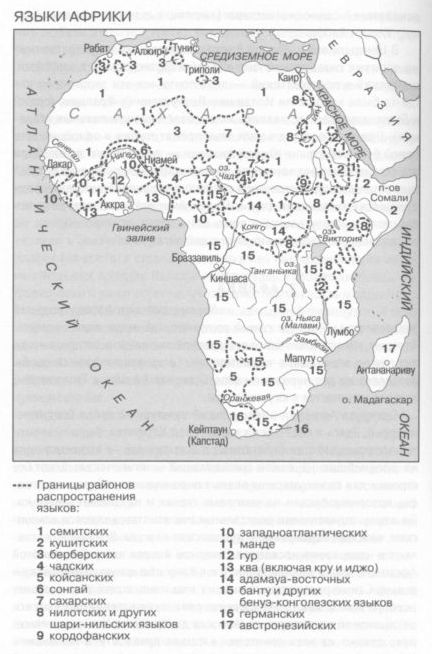

3. Africa

Scientists consider Africa the birthplace of mankind - this is the very continent where people lived "always". It is not known exactly who these were. ancient people and whether any of their descendants are still on earth. Today's Africa is, as it were, divided into two unequal parts: North Africa and Tropical Africa, which begins south of the Sahara.

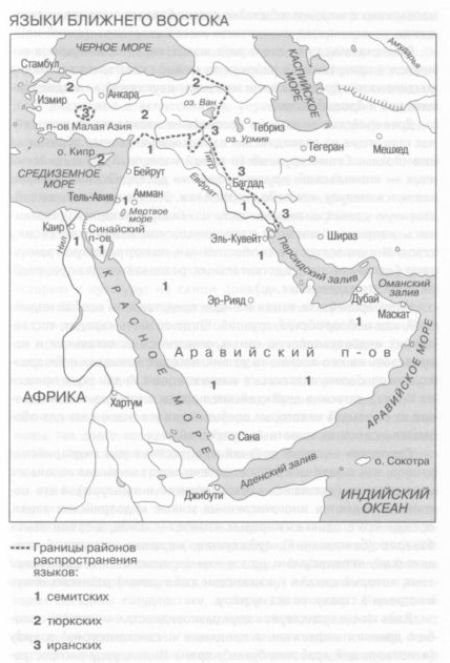

North Africa is an ancient Mediterranean cultural area. Here at one time stood the city of Carthage, there was the famous Alexandrian library, and even earlier - one of the oldest civilizations on earth - the Egyptian one - arose. The Egyptians built pyramids for their dead masters and invented hieroglyphs, which they used to write on stone steles and on papyrus scrolls. In terms of language, the distant relatives of the Egyptians are the Semitic, Chadic, Berber and Cushite peoples. All of them now make up the population of northern and even parts of Tropical Africa, and their languages are combined into one vast Afro-Asiatic family. The most widely spoken of these languages today are Semitic. From Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, the Semitic peoples settled over a vast territory from Morocco to Iraq, from Malta to Nigeria; however, of all the Semitic peoples of antiquity and the present time (Akkadians, Jews, Phoenicians, Aramaeans, Assyrians), only Arabs and Ethiopians found themselves in Africa. But the Arabs from the VIII century began to live in North Africa everywhere - in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Egypt. It was the Egyptian dialect of Arabic that supplanted the ancient Egyptian language and its descendant, Coptic, in Egypt.

The Chadic branch includes many dozens of languages spoken in areas adjacent to Lake Chad - in Nigeria, Cameroon and the Republic of Chad. Among these small languages, one giant language stands out - this is Hausa. The Hausa city-states were located in Northern Nigeria and neighboring countries, and is still understood by tens of millions of people in West Africa. Hausa - bright representative analytic languages, but it has both alternations and transfixes.

As for the Berbers, these are the descendants of warlike nomadic tribes, now living in small groups in Algeria, Mali, Morocco and some other countries. The most famous of them are the Tuareg; the Tuareg even had their own script - "square" letters of characteristic styles, which are written from right to left (as in other Semitic languages).

Cushitic languages are spoken by some of the inhabitants of Ethiopia, the upper reaches of the Nile and neighboring areas (once Egyptian pharaohs sent their warriors from the north to the distant and mysterious country of Kush, from whose name the Kushite peoples got their name). The largest language of this group is Somali, which is spoken, of course, in the state of Somalia.

And south of the Sahara begins the so-called Tropical, or Black, Africa. In this part of Africa, linguists count more than two thousand languages; these languages, like the languages of the indigenous peoples of America, are different, and yet scientists see between them family relations. It is believed that there are only three major language families.

First, Nilo-Saharan. The peoples who speak the languages of this family live mainly in East Africa, in the upper reaches of the Nile - in Kenya and Uganda. These are pastoralists. Among them, the Masai people are known (their language is called Maa) - one of the tallest in the world. Of the other languages of this family, the Songhai language is famous. Breaking away from their neighbors, the Songhai ended up in an "alien" area - Central and West Africa, on the territory of the present-day states of Mali and Niger. And here, oddly enough, among peoples completely unrelated to them, they took root, and not just took root, but founded the powerful Songhay empire, which lasted almost until the arrival of the French colonizers (this empire was destroyed by the Moroccan sultan only at the end of the 16th century). It was the Songhai Empire that owned the famous city of Timbuktu on the Niger River with the most beautiful mosque in West Africa.

The second largest family in Black Africa is the Niger-Congo. The peoples of this language family inhabit Western and all of Equatorial and Southern Africa. There are many in West Africa small groups languages. We can say that this is such a "linguistic cauldron"; they even believe that there is no other place on earth where the "density" of languages \u200b\u200bis so high. Remember when we marveled at the linguistic diversity of North America? thirty, fifty languages ... So, in West Africa (and, of course, in area it is much smaller than all of America) - there are many hundreds of languages. Among them are Fula, Wolof, More, Dogon, Malinke, Yoruba, and many, many others (some of these language names you came across on the pages of this book).

But starting from the equator, there are areas inhabited almost exclusively by the Bantu peoples - they also belong to the Niger-Congo family. These are perhaps the most famous African languages. Many different peoples speak Bantu languages, their total number now is over one hundred and sixty million people. Tireless travelers, the Bantu moved from Central Africa, from the region of the African Great Lakes, to the south and west, and mastered new and new lands. And on these lands they founded states - with kings, warriors, priests and farmers, and the inhabitants adopted the Bantu languages - different, but very similar friend to each other, because the Bantu languages differ from each other no more than different Slavic ones; for example, the northernmost Bantu language differs from the southernmost a little more than Russian from Bulgarian. Even the pygmies living in the equatorial forests of Central Africa, the famous pygmies, differ from other Africans and appearance, and according to the way of life, as far as is known, they did not retain their own language: they also speak different languages Bantu. The largest Bantu language is Swahili. It is the trading language of the entire East Coast, from Kenya to Mozambique. In addition, the Lingala language is quite widespread - it is spoken in Zaire and the Congo. But in Cameroon, Uganda, Gabon, Rwanda, Mozambique, Angola, Zimbabwe, South Africa, they also speak different Bantu languages (the most famous are Zulu, Rwanda, Ganda, Luba, Duala, Herero, etc.).

The most striking feature of the Bantu is nominal classes (about what nominal classes are, it is written in the fifth chapter in the section "Grammatical gender"); almost any language chosen at random has at least ten different classes. However, there are nominal classes in other languages of this family, for example, in the Fula language, where, as is known, there are the most classes, in the Wolof language (Senegal), More (Burkina Faso), etc.

But the most surprising thing is that languages \u200b\u200bthat do not look like Bantu or Fula belong to the same family. These are languages almost devoid of grammatical categories, approaching in type to the isolating languages of Southeast Asia. They are combined into two groups - the Kwa group and the Mande group. The Kwa peoples (the most famous of them are the Yoruba, Ewe and Akan - we also talked about them in the book) live on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, from Ghana to Nigeria, and the Mande people live in Guinea, Mali and neighboring countries.

We went from north to south, covering almost the entire African continent - but there is one more family of languages left! Where do speakers of these languages live? In a very small space in South Africa, in Namibia, in the terrible Kalahari Desert. Do people really live here? Yes, these are the Bushmen - the people of the bush. This is one of the most mysterious peoples on the ground. Bushmen and, possibly, related Hottentots (they also live in southern Africa) differ from other Africans in appearance (they have yellow skin and slanted eyes), and by their culture (these peoples hardly know agriculture, they are engaged in hunting and gathering). Or maybe they are the descendants of the ancient inhabitants of Africa, pushed aside by the Bantu peoples to the south? The languages of these peoples belong to the Khoisan family; they are famous, for example, for their sound systems: in some of them, the largest number of sounds on earth is more than a hundred (and you remember from the fourth chapter that there are usually thirty to forty sounds in a language, and even in such languages as Dagestan, the number of sounds does not exceed seventy or eighty), besides, special “clicking” or “smacking” consonants are found in abundance (we also talked about them at the beginning of the fourth chapter).

European languages in Africa. In Africa, three European languages are mainly spoken - English, French and Portuguese; all these are the languages of the former colonies: English, French, Belgian, Portuguese. In one small state of Tropical Africa, Spanish is used: this is the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, with its capital on the island of Bioko in the Gulf of Guinea (formerly this island was called Fernando Po). There were also German colonies in Africa, but Germany lost them - after the First World War they were divided between England, France and Belgium.

French is still spoken in most West African countries (although not all), as well as in Chad, the Central African Republic, the Congo and some other countries, including former Belgian colonies such as Zaire or Rwanda. The Portuguese language is spoken primarily in Angola, Mozambique and small Guinea-Bissau, but in other countries of Tropical Africa, such as Nigeria and Ghana in the west, Kenya in the east or Zambia and Zimbabwe in the south, English is used. But in Cameroon, English and French are both official languages. As for the Republic of South Africa, many Europeans still live there; these are the descendants of Dutch settlers (Boers) and the British. The Boers speak Afrikaans, which is closely related to Dutch.

It must be said that in almost no country in Africa, local languages are not state languages - the only exceptions are, perhaps, Tanzania (with the Swahili language) and Somalia (with the Somali language of the Afroasian family). Moreover, in Africa, not many languages are written. Generally speaking, there are reasons for this, which we partly discussed in the third chapter. Here I would only like to draw your attention to the difference that is found between the role of the European language in the west of Africa (in the former French colonies) and in its east and center (in the former English colonies).

The fact is that the French usually forced to study their language - in all colonial schools it was taught from the first grade in without fail. The English are in primary school they used local languages for training and only then, already minimally educated people, that is, people with completed primary education who voluntarily agreed to study further, taught English. If we compare what came out of it, the picture will be very interesting. Firstly, local languages developed better in the English colonies - for example, newspapers are published in many of them, and large ones such as Swahili or Hausa even have their own literature; in French - the situation was much worse: there was not only no literature and newspapers, but even the overwhelming majority of local languages \u200b\u200bdid not have written language.

On the other hand, the French language itself has survived in Africa much closer to its original European version than English. Some variants of English have turned into special languages - the so-called Creole. What is it?

You know, there are times when a person has to communicate with a foreigner, but he does not have time to learn the language. Then communication takes place in the so-called "broken" language, or pidgin, - like "your-mine-understand-no." Meanwhile, such a situation can arise not by chance, in the life of one person, but by force and with entire groups of people. Very often this happens when masters communicate with slaves in their own language or when Europeans come to trade with people who speak a language they do not know. With such communication, fragments of words are connected, as it were, on a living thread, and such semi-languages, of course, have no grammar. But then some of these languages "on hastily"can - under favorable conditions - suddenly begin to develop further: imagine, slaves from different places taken to an island common language, except for the pidgin, they do not have, you have to adapt everything to new and new needs. And if children are born in their families, then this language becomes their native language, and from that moment it ceases to be a pidgin and is called Creole. This is a full-fledged language, only it has lost all the grammar of its ancestor language.

So, as a result of the different African policies of the French and the British, it turned out that there are a lot of English-based Creole languages, and there is not a single French-based one in Africa (although such languages are rarely found outside of it, for example, on the island Haiti in the Caribbean); as for Portuguese, there is only one such Creole - in the Cape Verde Islands off the west coast of Africa.

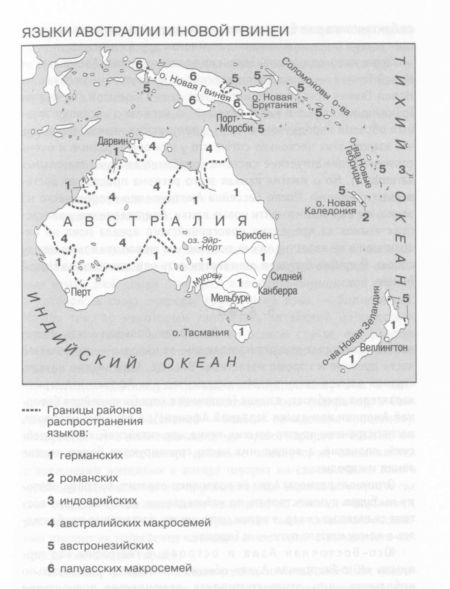

4. Australia and New Guinea

The features of Australia are primarily related to its remoteness from other countries and continents - remember the famous marsupials, which, except in Australia, are found almost nowhere in the world. And the Australian languages are also not like other languages of the world. At least they haven't found any relatives yet. There are about two hundred languages in Australia; many of them are now on the verge of extinction - they are spoken by no more than a few hundred people. kinship various groups these languages have not been proven among themselves either, so now there are more than ten different language families in Australia. The main and most numerous of them is one - this is the Pama-nyunga family; the languages of this family also occupy the largest territory, primarily in the north and east of the continent. What are these languages, from the point of view of a typologist? They are ergative and agglutinative (we talked about the special ergative case in the fifth chapter, in the section on cases, and what languages are called agglutinative, it is said in the sixth chapter of the book). They have suffixes and almost no prefixes. There are, as in African languages, consonant classes, but not many - usually no more than four or five. Sometimes there is incorporation (and what is incorporation is also written in the sixth chapter). The most famous language of this family is the Dirbal language. Describing it, the British linguist Richard Dixon created an exemplary grammar of an exotic language (all the typologists of the world know it); the Dirbal language was exhaustively described by him about twenty years ago, and then ... disappeared.

Now in Australia, a whole institute for the study of Aboriginal people has been created, so we can hope that soon we will learn not only about the Dirbal language, but also about many other interesting languages \u200b\u200bof Australia.

Of the European languages in Australia, English is primarily used, of course, only Australian English differs from British English even more than American. For example, there is a different vowel system and, of course, a lot of different vocabulary.

Only one narrow Torres Strait separates Australia from New Guinea - but the linguistic (and cultural) landscape in New Guinea is completely different. This largest (not counting Greenland) island in the world, similar to a turtle, is inhabited mainly by peoples who speak Papuan languages. It is known that there are several hundred of these languages, that they have very different and very complex grammatical systems (especially systems of verbal categories). But there is simply no reliable information about many languages of this region. After the Amazon basin, this is the second place on earth where you can still find new languages. Relatives of the Papuan languages outside the New Guinean area have not yet been found, and it is not known for sure whether all these languages are related to each other. I think future linguists have something to do in New Guinea.

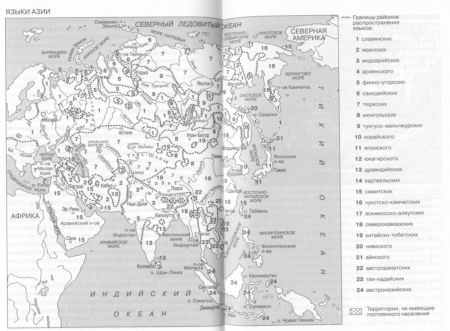

5. Asia

This is the largest part of the world; the languages spoken by the peoples inhabiting it are for the most part ancient and well known. In general, Asia can be called a country of giant languages. We have seen that Africa and America are characterized by fragmentation of languages (remember, for example, the Indians of North America or the languages of West Africa!); in Asia, on the contrary, "super-languages" such as Chinese, Hindi, Arabic, Japanese are common, and smaller languages and peoples often cluster around them.

The vast size of Asia does not allow us to cover it at once, so we will travel through it slowly, moving from the southeast, first to the north, and then again to the south, gradually approaching the end of our journey - to Europe.

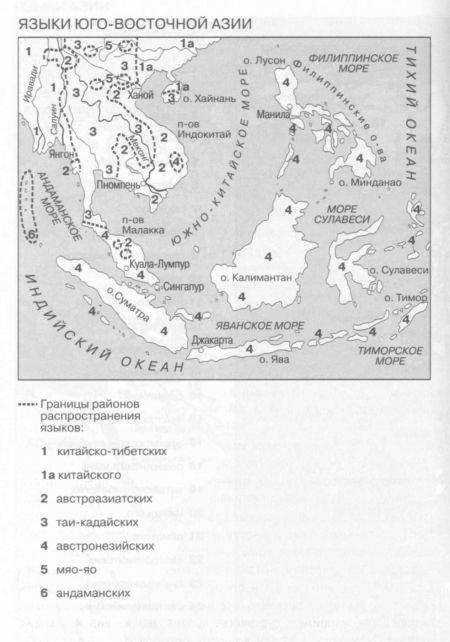

Southeast Asia and islands. In geography, the term "Southeast Asia" usually refers to a relatively small part of this continent, including the peninsulas of Indochina, Malacca and nearby islands. But it will be more convenient for us if we slightly expand these conditional boundaries, including in the north - China, in the east - all the islands of Oceania (even those that are located closer to America than to Asia or Australia); and finally, in the west, we need the island of Madagascar (which, for a geographer, is almost part of Africa). I think geographers will forgive us for this somewhat free treatment of countries and seas - what can you do, the interests of linguistics and geography do not always coincide exactly.

So, in all this vast space, four largest families of languages stand out. They are called like this:

Sino-Tibetan;

- Thai;

- Austroasiatic;

- Austronesian.

We will consider each of these families in turn. The main language of the Sino-Tibetan family is, of course, Chinese; the remaining languages of this family belong to the Tibeto-Burmese group, in which, in turn, the largest language is Burmese. Meanwhile, according to some hypotheses, Chinese is not related to the rest of the languages of its family; in any case, its kinship with them is more difficult to prove than the kinship of all other languages among themselves.

There are already more than a billion Chinese on earth, and they live not only in China, but throughout Southeast Asia (for example, in Singapore, the Chinese population is more than seventy percent). It is interesting that in these countries, among foreign peoples and languages, the Chinese, as a rule, live rather closed, do not mix with the indigenous people and always speak their own language. Many Chinese are also moving to large cities in Europe and America, where they have created entire Chinatowns, with their own shops, restaurants, banks, etc.; about the size of such Chinese settlements says their English name China town, that is, simply "Chinese city".

Since China is a large country, the Chinese language is very heterogeneous. Generally speaking, this does not always happen with large languages in large areas (one of the exceptions is just the Russian language), but more often it happens exactly like this: we know this from the example of American and Australian English, Arabic can also serve as an example, which will be discussed below.

Therefore, in essence, there are many Chinese languages: dialects of Chinese could be safely considered different languages, because representatives of different dialects often simply do not understand each other. In particular, there are very significant differences between the "northern" and "southern" (more precisely, southeastern) Chinese dialects - a resident of Beijing or Harbin (the city of Harbin, as you know, is located in northern China), a resident of Shanghai (this is the center of China) and a resident of Canton (south of China) is unlikely to understand each other. But at the same time, the inhabitants of all these regions of China are aware of themselves as belonging to a single people and call themselves Han.

The Chinese are not only the largest people in the world, but also the people with one of the oldest written histories. The states on the territory of modern China (with their rulers, warriors, fortresses and the first samples of writing-drawings!) have existed since at least the second millennium BC. e.; The first monuments of the ancient Chinese language date back to the same era (by the way, these were divinatory inscriptions). Thus, of the living languages, the Chinese language is perhaps the language with the oldest history (after all, the first samples of Chinese writing are older than, for example, Hittite cuneiform tablets - but not a trace of the Hittite language has long been left on earth).

Of course, ancient Chinese is very different from modern Chinese. Nevertheless, both of them are isolating in their structure, as are the vast majority of the languages of this region: after all, not only other languages \u200b\u200bof this family (that is, Tibeto-Burmese) are isolating, but also all Thai and Austronesian, and these are typical representatives of isolating languages: there are no or almost no grammatical indicators, short monosyllabic words; in addition, all the languages of this family, as well as Thai and many Austroasiatic ones, are tonal (and about what tones are, it is written in the fourth chapter of the book, in the section on stress). So, both modern and ancient Chinese - both can be considered isolating, but in modern language, unlike ancient, there are still some non-root morphemes - for example, suffixes denoting the form or tense of the verb. There are, of course, an insignificant number of such morphemes in it compared to the non-isolating languages familiar to us, but if we compare it with ancient Chinese, it will look like a language that has gone far from the state in which the "correct" isolating one should really be. language. In this sense, Thai and such Austroasiatic languages as, say, Vietnamese, are closer in structure to Old Chinese, while modern Chinese can be compared with such a territorially distant (and typologically close) language as the Yoruba language.

The Tibeto-Burmese languages are concentrated, as their name suggests, mainly in the mountains of Tibet and in the territories adjacent to them: these are the southeastern and southern parts of China (some areas of Tibet were captured by China quite recently, in the middle of the 20th century), Myanmar ( former Burma), mountainous Nepal and northeastern India and other countries. The largest languages among them are Burmese and Tibetan (different dialects of which are spoken by the inhabitants of the Tibet region of China, the Sherpas of Nepal and other peoples). In their structure, these languages are closest to the isolating type, but, like modern Chinese (and even, perhaps, to a greater extent), they are languages with "non-strict" isolation, with elements of analyticism and agglutination.

The Thai family includes the languages spoken in Southern China, Laos and Thailand; the main languages of this group are Lao and Thai, typical isolating languages.

The Austroasiatic (from the Latin root Austr, "south") family includes such languages as Vietnamese and its closest relative, Muong, Khmer (in Cambodia) and other lesser known and significant languages of Southeast Asia. Usually these are tone isolating languages that were under strong influence Chinese, but not related to it. On the territory of India, the languages of the Munda group are common - this is a special, western branch of the Austroasiatic family; the Munda languages (perhaps under the influence of neighboring Dravidian and Indo-Aryan languages, which we will talk about a little later) turned out to be the only truly non-isolating ones among their Austroasiatic relatives; however, in fairness it must be said that they are no longer located in Southeast Asia - this indisputable "kingdom of isolating languages". The largest of the Munda languages is the Santali language, which is spoken by more than five million people. In addition, on the Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean, belonging to India (and if you look at the map, you will see that these islands are still located closer to Southeast Asia), they speak a special Nicobar language, which is also included in this family , but forms a separate group.

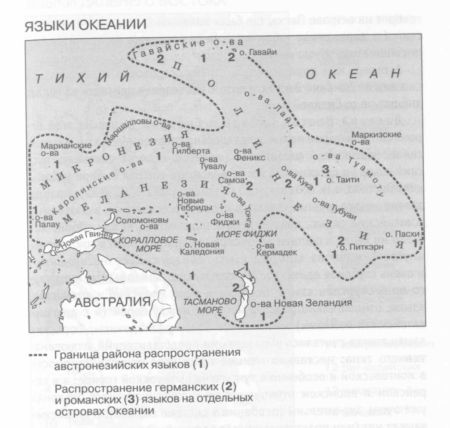

The Austronesian family (that is, "south-island": the Greek root - nes- is added to the Latin root of Austrian, which means "island": the same root is present, for example, in the Greek name Peloponnese) is a large association of languages \u200b\u200bdistributed mainly way on the islands of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, between Asia and Australia. It so happens that the speakers of these languages almost all live on large or small islands: these are the islands of Polynesia scattered throughout the Pacific Ocean (literally "many islands"), Melanesia ("black islands") and Micronesia ("small islands"), this The Philippine and Sunda Islands between the Indian and Pacific Oceans and, finally, this is the island of Madagascar off the very coast of Africa, which was also once inhabited by immigrants from Indonesia. Speakers of special Austronesian languages also live on the island of Taiwan, the main population of which is now Chinese.

Close to each other in structure (and often combined into one branch) are the Filipino languages (Tagalog, Ilokano, and many others) and the languages \u200b\u200bof many peoples of the Sunda Islands living in two states - Malaysia (occupying part of the island of Kalimantan - aka Borneo - and part of the Malay Peninsula) and Indonesia (spread on such large islands as Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and even annexed part of New Guinea - this is not counting the many small islands and islets). The state language of Malaysia (Malay) and Indonesia (Indonesian) are so close to each other that, in fact, they could be considered variants of the same language, having in different states different names(like Norwegian and Danish or Romanian and Moldovan). Indonesian is a somewhat simplified variant of Malay, believed to have originated from trade between different nations islands. Both of these languages were strongly influenced by Sanskrit, which was the ancient language of the Indian rulers of Indonesia; with the advent of Islam to these lands, the influence of the Arabic language began (until recently in Malaysia, they wrote in Arabic letters).

Of the European languages, English (in Malaysia), Portuguese and especially Dutch (in Indonesia, which was a colony of the Netherlands for more than three hundred years) were widespread here.

The largest people in Indonesia are the Javanese, who speak the Javanese language; this language is remarkable in many ways. For example, it has an unusual great development received means of expressing politeness: depending on the attitude towards the interlocutor, a Javanese speaker can use one of three different "languages" (that is, naming the same concepts in different ways!). Literature in the Javanese language is one of the most ancient in Indonesia (the first monuments in the Old Javanese Kawi language, written in a special Old Javanese script, date back to the 9th century - these are contemporaries of the first Slavic alphabet).

The Malagasy language, which is spoken by the inhabitants of the island of Madagascar off the coast of Africa, belongs to the same subgroup of languages (the whole of it is often also called "Indonesian") - the descendants of immigrants from Indonesia, mixed with the local African population.

The Indonesian languages are another example of languages with a pronounced agglutinative structure; they are dominated by prefixes, there are infixes and there is a very peculiar verb system with many derivative forms.

The peoples of Oceania speak languages belonging to another branch of the Austronesian family, but their kinship with the Indonesian languages has been established quite reliably. These are the Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian languages, common on all the islands of Oceania - from Hawaiian Islands to New Zealand. Most speakers are:

From the Polynesian languages \u200b\u200b- Maori ( New Zealand), Samoa, Tonga and Tahitian (islands of eastern and southern Oceania);

From the Melanesian languages - Fijian (Fiji Islands);

Of the Micronesian languages - Kiribati (Kiribati Islands in the heart of the Pacific Ocean).

In their structure, all these languages are agglutinative and analytical: few morphemes are attached to the root, but there are many auxiliary words that express quite diverse grammatical meanings. Even an indicator, for example, of the past tense, is often a special particle that is at the very beginning of a sentence, and after it comes the verb and all other words. Cases and number of nouns can be denoted by special particles. Another peculiar feature of these languages (especially Polynesian), which noticeably distinguishes them from other languages of the world, is big number consonants. Therefore, vowels are used in speech much more often than in other languages; many words are almost all vowels. This is noticeable even in the melodic names of these languages, which sound like strange music, reminiscent of coral atolls and palm trees over warm ocean water: Wolvai, Niue, Rapanui (this is the language spoken on Easter Island, where mysterious stone statues and wooden tablets with the still unread letter kohau rongo-rongo).

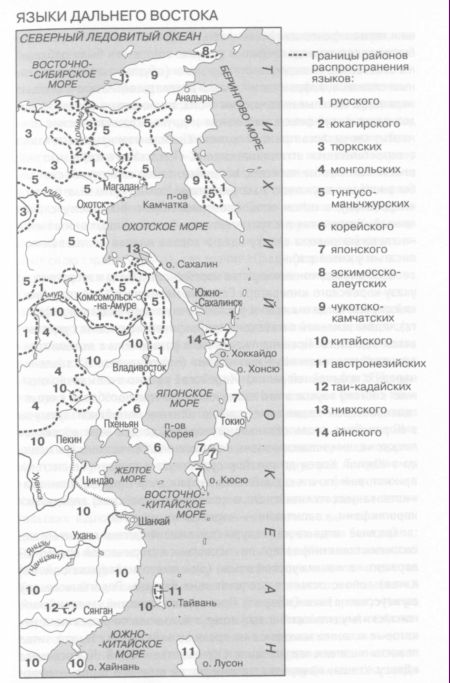

And now it's time for us to leave the country of the islands and move first to the Far East, and then, gradually moving west, to reach Central Asia.

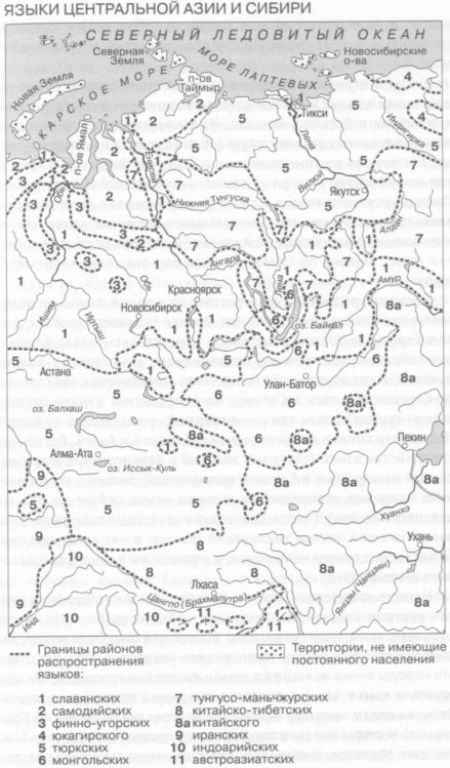

Far East, Siberia and Central Asia.

This vast territory is almost completely dominated by the languages of one family, called Altai (of course, if you do not take into account the Russian language, but the Russians are still not the original inhabitants of Siberia and the Far East, they appear there only from the 16th-17th centuries); however, not all scientists agree that all the languages included in the Altaic family are really related to each other. Be that as it may, three groups are distinguished within the Altaic family, within each of which languages reveal an undoubted and very deep unity. These are Turkic, Mongolian and Tungus-Manchu languages; Japanese and Korean languages, regarding the relationship of which among themselves (and with other Altaic languages), opinions are even more contradictory. Turkic languages have always been considered exemplary representatives of the agglutinative type; somewhat less signs of agglutination in the Mongolian and especially in the Tungus-Manchu group; and in Korean and Japanese, deviations from the "agglutinative standard" are already very significant (especially in the verb system). There are no (or practically no) prefixes in the Altaic languages and the category of grammatical gender is completely absent.

Japanese is one of the largest languages in the world, although as a state language it is spoken only in Japan. It is very likely that in ancient times some Austronesian peoples also lived on the Japanese islands (close, in particular, to the natives of Taiwan); in any case, linguists find similarities not only between Japanese and Altaic, but also between Japanese and Austronesian languages. IN early periods the history of the Japanese language a huge impact Chinese language (comparable, for example, with the influence of the old French to English); not only many hundreds of words were borrowed from the Chinese (and many thousands more common words of the Japanese language were later compiled from Chinese roots), but also hieroglyphic writing. Later, Chinese characters were somewhat modified and, in addition, Japanese syllabic characters proper were added to them (the common name for different syllabic alphabets is "kana"); now, usually with the help of a hieroglyph, the root of the word is written, and with the help of one of the types of kana - suffixes, endings and other grammatical elements: this is how the writing of an isolating language was reconciled with the needs of an agglutinative one. Imagine that instead of writing, for example, the word solar, we would first draw a circle resembling the sun (this would be our "hieroglyph"), and then calmly attribute to it on the right - eternal. This is exactly what the Japanese do (only they usually write not from left to right, but from top to bottom and from right to left - this is how the Chinese write too).

Koreans use a special script: it was invented by order of the Korean emperor Sejong the Great in 1444 (a rare case when we can indicate the exact date the creation of the alphabet) to replace the pre-existing Chinese character script. The rules of writing were explained in a special treatise called "Hong-min jeonum" (which means "Instructions to the people about the correct speech"). The Korean script very accurately reflects the sound system of this language and is well adapted to its agglutinative grammar, but the influence of Chinese culture in Korea was so strong that until the 19th century, the Korean script was used very limitedly. It is now recognized, but South Korea there is still a mixed system in which (almost like in Japan) the roots of words (though only borrowed from Chinese, and not native Korean) are transmitted in hieroglyphs, and the endings in Korean characters.

The once formidable Manchus (who ruled China for several centuries) are now almost gone from the historical arena; Manchu speakers (they live in the northern regions of China) are now less and less. The related Tungus languages of Siberia and the Amur region (Even, Evenki, Nanai, Udege, etc.) are also very few in number, and some are even on the verge of extinction. Those who read the story of the writer, naturalist and traveler V.K. ), that is, just a representative of one of the Tungus-Manchurian peoples.

The Altai Mountains and the steppes adjacent to them are the ancestral home of the nomadic Mongols and the ancient Turks. In search of new pastures for livestock, they could travel great distances (especially in dry years); from the ninth century BC. e. their militant detachments began to threaten China - this is to protect against the nomadic Xiongnu (apparently, Turkic-speaking), the Chinese emperors ordered the construction of the Great Wall of China in the north of the country. The Mongolian-speaking Khitan (who conquered the north of China and Manchuria) even gave their name to China: it is believed that in Russian the word China is associated with this people (after all, the Chinese themselves call their country Zhong-guo, which means "Middle Empire", and all European peoples derive its name from ancient word Hina of unknown origin).

In a series of changing conquerors who subjugated the Turkestan steppes and the Mongolian plains, the biggest mark was left, of course, by the invincible Genghis Khan, the head of all the Mongols, who conquered a huge part of the Asian world in the 12th century - from Korea to Asia Minor; it was his grandson Baty (in Mongolian Vatu) who ravaged Russia in the 13th century. Relatives and descendants of Genghis Khan and Batu eventually conquered even China (although not on long time), subjugated Burma and India (the Mughal Empire), took possession of Baghdad and Damascus! In the XIV century, the palm passed to another formidable conqueror - the Turkic Tamerlane, or Timur-lang ("lame Timur"); true, and he liked to pretend to be a descendant of Genghis Khan. The modern territory inhabited by speakers of the Mongolian languages, of course, cannot be compared with the size of the short-lived empires of Genghis Khan or the terrible Tamerlane. There are three main Mongolian languages: this is actually Mongolian (aka Khalkha), geographically and linguistically close to it, the Buryat and Kalmyk languages, whose speakers turned out to be the will of history in the Volga steppes (that is, already in Europe). Smaller languages of the Mongolian group are common in northern China. All modern Mongolian languages are relatively recently (after the 16th century) divided descendants of a single language close to Old Mongolian (it was in this language, in all likelihood, that Genghis Khan still spoke); Old Mongolian, the language of ancient Buddhist manuscripts and historical chronicles, had its own special "vertical" writing system. It is still used as a written literary language in China and partly in Mongolia itself (mainly in the religious sphere). Modern Mongolian languages are close to each other; all of them are distinguished by "non-strict" agglutination, a developed system of cases and verb forms (in particular, moods). By the way, the Russian word bogatyr goes back to the ancient Mongolian word: in the modern Mongolian language it has the form baator (this word is part of the name of the capital of Mongolia - Ulaanbaatar, which means "red hero").

The fate of the Turkic peoples, as you already understood, was closely intertwined with the fate of the Mongolian peoples: the same nomadic transitions, the same raids, conquests, formidable commanders who instilled fear in the cities of Asia and Europe (by the way, the very word Turks is of Mongolian origin). However, Turkic speakers turned out to be much more numerous and settled over a vast territory from Yakutia to Turkey. Nevertheless, all Turkic languages show an amazing similarity of grammatical structure and a great similarity of vocabulary. A similar situation (many very close languages dispersed over a large area), perhaps, exists only in the linguistic area of the Bantu peoples (however, there are many more Bantu languages). The Turks founded states on the Volga, in Siberia, in Central Asia and Asia Minor (sometimes united in big empires, and more often - existing separately). The descendants of the Turkic-speaking people of the Bulgars, by the way, are to some extent the modern Bulgarians, who adopted the language of the South Slavic population of the Black Sea region, but retained their Turkic name. The modern Chuvash is closest to the language of these ancient Bulgars.

Of all the Turkic languages, Chuvash (which was strongly influenced by the languages of the neighboring Finno-Volga peoples - Mari and Mordovian) and Yakut have the greatest differences. The rest of the Turkic languages, as we have already said, are very close to each other. Two main groups of "large" Turkic languages are often distinguished: these are Kypchak (which includes Altai, Tatar, Bashkir, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Balkar, Kumyk and other languages; Uzbek is also close to the Kypchak languages) and Oghuz (which includes Turkish, Azerbaijani and Turkmen languages).

But let the huge language families of Asia not obscure from us several small and very small, but very interesting languages of Siberia and the Far East. Of the relatively large families, we will name the Eskimo-Aleut (we spoke about these languages above, since they are also common in North America) and the Chukchi-Kamchatka (the main languages are Chukchi and Koryak). In my own way grammatical structure(incorporation with long sentence words, an abundance of verb forms) these languages are close to the languages of the Indians of North America (we talked about this in the sixth chapter), but this family stands apart in terms of vocabulary.

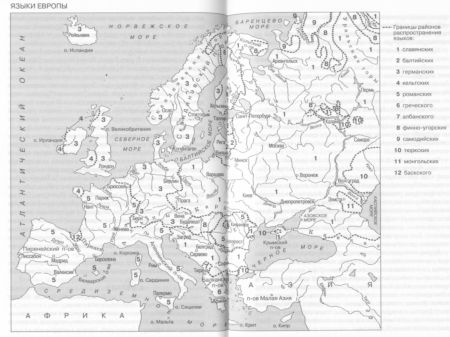

The large Ural family consists of a powerful Finno-Ugric branch, which gradually moved almost in its entirety from the Urals to Europe; beyond the Urals, in the upper reaches of the Ob, only the Khanty and Mansi, closely related to the modern Hungarian, remained. But another, small branch of the Samoyed languages almost entirely remained in Siberia. Of the Samoyedic languages, only one is relatively large - Nenets; The Nenets live on the coast of the Arctic Ocean, on the border between Europe and Asia. The rest of the Samoyedic languages (northern Enets and Nganasan and the Selkup scattered between the Ob and the Yenisei) are close to extinction; for example, there are no more than twenty people who speak the Enets language now! Among other things, the Samoyedic languages are famous for a large number verb moods: they even have a special “hearing” mood, which we talked about a little in the fifth chapter.

Several peoples of Siberia and the Far East speak languages for which no relatives could be found. They are sometimes called Paleo-Asiatic, meaning that they may be the remnants of the languages of the most ancient population of these places. All these peoples are very few, some have almost disappeared or lost their language. These are the Yukaghirs living in the upper reaches of the cold Kolyma, the Nivkhs living in the Far East (on Sakhalin and in the Amur region), and the Kets inhabiting several villages along the banks of the Yenisei and its tributaries. Both the Nivkh and Ket languages are characterized by exceptionally complex verbal systems, and the Nivkh language also presents complex consonant alternations, somewhat similar to those that the Celtic languages are justly proud of. The Ainu language is also lonely, which is spoken (more precisely, they spoke, since there are no longer those who speak this language as their native language) the descendants of the most ancient population of Japan, living in the north of this country (Hokkaido Island) and until recently lived on Sakhalin Island. The Ainu differ from the Japanese in appearance (remember, in the same way, the Bushmen in southern Africa even differed in appearance from the Bantu aliens); for a long time in Japanese society, they occupied a subordinate position, considered "unclean". Now the descendants of the Ainu have switched to Japanese and, in general, have completely merged into Japanese society.

Caucasus. The Caucasus and Transcaucasia is the only region of its kind on the linguistic map of the world, where such a large number of languages are concentrated in such a small area, and the most diverse, including unrelated ones. A similar variety, even variegation, can be observed in North America and West Africa, but there, nevertheless, languages occupy vast spaces, and do not adjoin each other: after all, for example, in Dagestan it often happens that the inhabitants of two neighboring mountainous villages speak completely different languages and cannot understand each other.

When they say "Caucasus", then this is often understood not only as the mountains of the Greater Caucasus Range, but also the regions adjacent to them from the north (Northern Caucasus) and from the south (Transcaucasia). We will do the same.

"On the outskirts" of the Caucasus are Turkic-speaking peoples: Nogais, Kumyks, Balkars and Karachays (Karachay and Balkar languages are very close; all of these languages are included in the same Kypchak subgroup of Turkic languages - together with Tatar and Kazakh). In the very heart of the Caucasus, in its high mountainous part, peoples of two different language families live: the Abkhaz-Adyghe and the Nakh-Dagestan.

Abkhaz-Adyghe peoples - inhabitants North Caucasus and the Black Sea coast (their range is, as it were, split in two by Turkic-speaking Karachays and Balkars); The Abkhaz-Adyghe family includes, respectively, the languages of the Abkhazian (Abkhazian and Abaza) and Adyghe subgroups (Adyghe, Kabardian and Circassian), as well as the extinct Ubykh. These are very peculiar languages, the structure of which is somewhat close to both the Bantu languages and the languages of the North American Indians, but is not exactly similar to either of them. In these languages there are only two or three different vowels, but there are seventy-eight-ten consonants; nouns have almost no grammatical categories, but a monosyllabic (often even monosonant) verbal root can be joined (both in front and behind, but mostly in front) by a very long chain of various suffixes and prefixes - from indicators of direction of movement to indicators of person, number and the gender of the subject and all (!) Complements of the verb. For example, what we could express in Russian with a sentence:

Didn't I, along with you, force her to give it to him? -

in the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages it could well have been expressed with only one (and at the same time not very long!) word - the form of the verb "give".

The extensive Nakh-Dagestan family unites the languages of the mountain peoples of Dagestan; this is the most amazing example and linguistic diversity, and extraordinary linguistic richness. Linguists will never cease to be amazed at the extraordinary complexity of the sound and grammatical structure and the extraordinary richness of the Dagestani languages. A verb in these languages can freely form hundreds of thousands (!) of forms, and we have already talked about the number of cases of a noun in the Dagestan languages more than once - this is a world record. In their structure, let me remind you, these are agglutinative languages, generally preferring suffixes to prefixes; almost all of them have the category of a nominal class, and the number of cases, in addition to numerous spatial ones, necessarily includes the ergative.

The Nakh-Dagestan family breaks up into the Nakh languages (close to each other Chechen and Ingush) of the North Caucasus and several groups of Dagestan proper languages in mountainous Dagestan; the largest of these languages are Avar, Dargin, Lak, Lezgin and Tabasaran (of which only the last two are closely related to each other). These five languages are written, the rest (there are at least two dozen of them) are almost all unwritten, often they are spoken only in some one village lost in the mountains.

But this is not all: in Transcaucasia we find representatives of three more different language families. These are, of course, Georgian, Armenian, Ossetian and Azerbaijani languages. Linguistically, there is practically nothing in common between them. Azerbaijan language(speakers live in Azerbaijan and northern Iran) - a typical representative of the Turkic language family (we talked about it a lot before); it is very close to the Turkish language and also to Turkmen.

Georgian language belongs to the Kartvelian family of languages; together with him, this family includes the Svan, Megrelian and Laz languages, whose speakers (both the mountaineers-Svans, and the inhabitants of western Georgia, the Mingrelians, and, perhaps, the Lazians living in the northeastern part of Turkey) are more likely to consider themselves Georgians (degree linguistic fragmentation and within Georgia itself is very large: there are differences in the speech of the inhabitants of Kartli, Imereti, Kakheti, Adjara). In its structure, the Georgian language is remotely similar to the languages of Dagestan (the same abundance of consonants, the ergative case - however, already without a large number local cases; richness of verb forms; but nouns have no category of gender/class). However, in terms of vocabulary, it does not reliably approach either the languages of Dagestan or any other languages of the world (for example, attempts to prove the relationship of the Georgian and Basque languages have not been recognized as convincing). The Georgian language uses its own special alphabet - you must have seen these beautiful, whimsically wriggling letters.

The Armenian language is an isolated representative of the Indo-European family, forming within this family, like the Greek and Albanian languages, an independent group. Before the arrival of the ancestors of the Armenians on the present territory of Armenia, there was a powerful state of Urartu, whose inhabitants spoke the Hurrian and Urartian languages; them family ties not defined, recently they have been trying to be associated with the North Caucasian languages. IN Armenian many Hurrian-Urartian borrowings. In general, the Armenian language has departed very far from the Indo-European model represented by the ancient Indo-European languages, although the most early form Armenian language (the so-called grabar, or "book language", known from the 5th century AD) is closer to this model. Agglutination is highly developed in modern Armenian; of all the Indo-European languages, it is the most agglutinative. The category of gender is also absent in the Armenian language.

We know the name of the creator of the Armenian alphabet: his name was Mesrop Mashtots (he also started the translation of the Bible into Grabar, which would later be called the "queen of translations", he is so accurate); Armenian letters, as if carved in stone, with their angular outlines, do not at all resemble the Georgian script. But in terms of sound richness, all the languages of the Caucasus can be compared. The poet Osip Mandelstam wrote about it this way:

The prickly speech of the Ararat valley,

Wild cat - Armenian speech.

Predatory language of adobe cities,

The speech of the starving bricks...

And also like this:

Your borderline ear

All sounds are good!